Scotland’s extensive and varied coast and sea support a staggering array of invertebrates and their habitats, including commercially exploited species such as crabs, lobsters, scallops, cockles and langoustine. Follow the links below to learn about just a few of our many special marine invertebrates.

Contents

Tube anemones

Two of the three tube anemones found in Britain are special to Scotland. The huge fireworks anemone Pachycerianthus multiplicatus is our most spectacular British anemone, and is a surprising animal to find living in soft mud at the bottom of Scottish sealochs. Arachnanthus sarsi is so rare that it doesn’t have a common name, and has only been found in a few places on the west coast. The little burrowing anemone Cerianthus lloydii, on the other hand, is extremely common almost everywhere in Britain, except for parts of the east coast

What are tube anemones?

Tube anemones are the only group of anemones that live in a mucus tube buried in the seabed. The tube is very slippery inside, so the anemone can slide rapidly into it when disturbed, disappearing completely into the seabed. All the tube anemones have two kinds of tentacles – long outer ones and a cluster of much shorter inner ones around a central mouth.

Why are they important?

The fireworks anemone and Arachnanthus sarsi are both Scottish specialities and are priority species for UK Biodiversity Action Plans now taken forward by the Scottish Government through the Scottish biodiversity Strategy

Fireworks anemone, Pachycerianthus multiplicatus

At up to 30 cm across, with a tube up to a metre long, the fireworks anemone is our biggest British anemone, and one of the most beautiful. Its crown has around 200 long outer tentacles, usually white with pale buff bands. The short inner tentacles may be the same colour, or contrasting yellow, pink or purple. The ends of the long tentacles drift with any slight current, giving them a characteristic kinked appearance. If touched gently, the tentacles each coil up tightly. In Britain, this anemone only lives in deep, soft mud in the most sheltered parts of sealochs, mainly the fjordic type with shallow sills and deep basins inside, at depths of 15-200 m. It also lives off the coast of Norway.

Arachnanthus sarsi

Very little is known about this beautiful anemone, because it is so rare. It has only been found at a few places in western Scotland, including the Firth of Lorn, and in north-west Ireland, in sandy or shelly mud at depths of 10-36 m. It has fewer tentacles than our other tube anemones, with only 30 outer and 30 inner, the latter often held together in a pointed cone. It may be more active at night, like some tropical tube anemones, and this may partly account for how rarely it is seen by divers.

Burrowing anemone, Cerianthus lloydii

The commonest and smallest of the tube anemones, the burrowing anemone has up to 70 long tentacles, with a span of about 7 cm. The colour is quite variable, but the outer tentacles are often translucent brown or opaque white. Some individuals have a beautiful bright green centre. The burrowing anemone lives in a wide range of sediments, from mud through to coarse gravel and maerl, from the lower shore to 100 m depth or more.

Northern sea fan, Swiftia pallida

It might seem surprising to find sea fans in cold Scottish waters, and they are certainly more typical creatures of the tropics, but the northern seafan (Swiftia pallida) thrives off our west coast. Although it looks plant-like, the northern sea fan is a colonial animal, related to soft corals. It grows up to 20 cm tall

Why is it important?

Nearly all the British records of the northern sea fan are from western Scotland, so we have a particular responsibility for this ‘national’ treasure. Both the northern sea fan and the rare sea fan anemone which lives on it, are priority species for UK Biodiversity Action Plans and have been taken forward by the Scottish Government as part of the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy .

Where does it live?

The northern sea fan has been found from Oban northwards to the east coast of Lewis. It also occurs in the Kenmare River in west Ireland, the only place where its distribution overlaps with that of the pink sea fan (Eunicella verrucosa), our only other British sea fan. The northern sea fan also occurs on the southwest coast of Scandinavia, and in much deeper water further south, in the Bay of Biscay and the Mediterranean (down to 600m)..

The northern sea fan usually grows in relatively sheltered, deeper water (below 20 m), on flat or sloping bedrock with some current but little wave action. These conditions are found off the east coasts of the southern Western Isles, at the entrances to some mainland sea lochs, and on deeper submerged reefs in the Minches. It often grows with cup sponges, the hard branched orange bryozoan (Porella compressa), and the deepwater northern feather star (Leptometra celtica), species that seem to thrive in similar conditions, and together they form a characteristic suite of animals.

How does it live?

The sea fan’s horny skeleton is covered with soft tissue, from which many small polyps with eight branched tentacles arise. The northern sea fan feeds by catching small animals in the plankton, and other food particles sinking from above, using sticky and poisonous nematocysts on its polyps. Many sea fans, as their name suggests, are fan-shaped, and often grow orientated across the water current to increase their chances of catching food. The northern sea fan has a rather straggly appearance, with loose branches not confined to one plane, perhaps (at least in deep water) because more of its food falls from above. Otherwise, little is known of the biology of this sea fan.

The rare sea fan anemone (Amphianthus dohrnii), which grows almost exclusively on sea fans (rarely on sea firs), has been seen occasionally on northern sea fans in the Forth of Lorn. Apart from taking up space, and perhaps competing for food, this little anemone appears to do no harm to its host, using it simply as a perch to raise it above the seabed. The anemone, which measures only about 1.5 cm across, reproduces by splitting at its base, which often results in several genetically identical anemones on the same sea fan. The sea fan anemone has apparently declined throughout its range in recent years

Northern feather star

The northern feather star (Leptometra celtica) is a graceful and curious echinoderm (from the Greek for spiny skinned) and is part of the class of crinoids (meaning “like a lily”). They have 10 long, slender arms that can be a variety of beautiful colours including yellow, white, pink-red or banded red and white. Their arms grow to 15cm long and are arranged around a central disc. Beneath this disc they have cirri that look like thin, stiff legs with hooks on the end that they use to hold themselves in place.

The northern feather star puts on a fascinating display when it exhibits its ability to ‘swim’ short distances through the water, which it does by flicking its arms up and down

The northern feather star is a filter feeder and positions itself where currents will pass over it. They hold their arms in the current and the pinnules (feathery looking branches on their arms) capture organic matter, a complex mixture of molecules suspended in the water, which is transported down the length of the arms to the mouth in the centre. The northern feather star is able to spread out its arms into a vertical fan across the current.

What is so special about them?

The northern feather star is normally a deep water species but western Scotland is unique in having shallow water examples in depths of around 20m in sea lochs and sheltered conditions. They can also form very dense aggregations in these environments and can be a significant component of the seabed community.

Where do they occur?

Northern feather stars are normally found in depths from 40 to over 1000 m depth, but are found in shallower waters in western Scotland. They are often found on shell-gravel, cobbles and different mixtures of sand, gravel, shingle and mud, as well as being associated with cold water coral reefs.

The species is abundant around the Minch, Skye and off the north coast of Scotland. There are only a few inshore British records outside Scotland. It has been found in deep water to the south and west of Ireland and the entrance to the English Channel.

What is the status of this species in Scotland?

Whilst there is not any information on the status of this species, a similar species the rosy feather star (Antedon bifida) is vulnerable to physical disturbance and removal by mobile fishing gear, changes in hydrology and habitat loss which may be caused by coastal or marine developments, substrate extraction for the aggregate industry, pollution and spoil dumping.

Are we doing anything to look after the northern feather star in Scotland?

This species is an SNH Priority Marine Feature and will be subject to new protection efforts deriving from the Scottish Marine Bill (including Marine Spatial Planning and new Marine Protected Areas).

Fan mussel, Atrina pectinata (fragilis)

The fan mussel is our largest British seashell, with the paired valves reaching an impressive 30cm long. These huge fan-shaped bivalves live with the pointed end buried in the seabed and the wider part sticking out, shells gaping slightly so the mussel inside can filter seawater

What is so special about them?

The shell is made of brown, horny material, which becomes rather flaky when dry, revealing beautiful mother-of-pearl beneath. The narrow, buried end of the fan mussel’s shell is anchored by strong byssus threads to a shell or stone. The beautiful, strong golden threads they make to attach their shells to the seabed have been used to decorate costumes for kings

The shells can be mostly buried in the sediment with only a small rim showing at the surface, or with up to a third of the shell visible. The exposed part becomes encrusted with other sessile animals like barnacles, tubeworms and encrusting seaweeds. From the upper end, which gapes slightly, the pale edge of the mantle emerges. This secretes new shell material around the upper edge as the mussel grows. The inhalant and exhalant siphons form two narrow openings; like other mussels, this mollusc feeds by filtering plankton from seawater sucked in through one siphon and expelled through the other. If disturbed, the animal can withdraw into the shell, but cannot close it completely. Because of their large size, it is thought that fan mussels are relatively long-lived. They reproduce by spawning into the sea, and there is concern that their current scarcity may make it impossible for them to reproduce successfully; individuals need to be close to each other to ensure fertilisation..

Where do they occur?

Records of fan mussels are mainly from the south and west of Britain, with most from western Scotland, so we have a particular responsibility for this spectacular mollusc. They live in sediment seabeds ranging from shell gravel to sand and soft mud, or mixtures of these, in depths from extreme low tide downwards. They are more common in offshore sediment plains, down to at least 600m deep.

What is the status of this habitat in Scotland?

Once common off British coasts, fan mussels have virtually disappeared from shallow waters above 50m. Even scallop divers, who spend much time searching the seabed, see them very rarely. Because they project from the seabed, they are easily snagged by bottom fishing gear, particularly scallop dredges. They have also been collected for ornaments by divers.

Are we doing anything to look after file shell beds in Scotland?

The fan mussel is protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, as amended by the Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004, and it has a UK Species Action Plan (as Atrina fragilis), now taken forward by the Scottish Government as part of the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy.

Horse mussel beds

In Gaelic, horse mussels (Modiolus modiolus) are called ‘clabaidh-dubha’ (‘clabby doos’), meaning ‘big black mouths’! This probably refers to how they look on a plate, but is also an apt description of them in the seabed, with the edge of the living mussel forming pale ‘lips’ inside the dark shell. Horse mussels are bivalve molluscs, similar to the familiar blue mussels of the seashore, but much larger at 10-20cm long, and they usually live below low water. The shell is solid and dark blue, with a glossy brown covering on the shells of live animals.

Why are they important?

Horse mussels form beds and reefs which stabilise mobile seabeds, creating a home for many other creatures, and good feeding grounds for young fish. Bottom trawls and dredges, particularly those used for scallops, are known to have caused widespread and long-lasting damage to some horse mussel beds, the best documented being in Strangford Lough, Northern Ireland. Horse mussel beds are a priority habitat for UK Biodiversity Action Plans , now taken forward by the Scottish Government as part of the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy .

Where do they live?

Horse mussels occur all around the British Isles, but they are more common in the north. The most extensive beds are off northern and western coasts, in depths of 5-70m, so in Scotland we have a particular responsibility for their care. Beds of mature horse mussels are not known south of the Severn and Humber Estuaries, and records from the far south are likely to be of single individuals or juveniles.

The mussels usually live part-buried in soft to coarse sediments, but can also attach to rock, from the lower shore to around 280m depth. They can live singly, or in small clumps, or can form extensive beds and reefs, especially in sheltered sites with tidal streams, as in the narrows of sealochs and the sounds between islands

Nature of the reef

The strong byssus threads of a horse mussel are like many tiny guy ropes, attaching it firmly to stones, shells and other mussels nearby, and anchoring it in the seabed. Many mussels together can form extensive beds. Sediments, shell fragments and mussel droppings accumulate between the live mussels, and the beds can build up over time into mounds or reefs which can be considerably higher than the original seabed. Young mussels settle between, and on top of, the older ones. When the older mussels die, their shells remain, helping to build up the height of the reef, and modifying the seabed considerably. Horse mussels are long-lived – many survive for more than 25 years old, and some may live to more than 50 years. Young mussels are a favourite meal for crabs and starfish, but once the mussels grow to more than 6cm long, they are relatively safe from these predators.

The mussels’ large shells provide a solid foundation for many sessile animals, including soft corals, tubeworms, barnacles, sea firs, sea mats and seaweeds. Young scallops attach to the sea firs. Between the shells, and inside older ones, brittlestars, crustaceans, worms, molluscs and many other small animals find shelter, attracting young fish (including commercial species like cod) to feed.

Flame shell beds

Flame shells (Limaria hians) are beautiful bivalve molluscs about 4cm long. They are also known as file shells.

Where do they occur?

In British waters, flame shells live only on western coasts, with the densest beds off west Scotland, mainly on seabeds of coarse sand, gravel and shells, from low water to around 100 m depth, often in areas with moderate or strong water currents. Individuals may also live under stones, or in kelp holdfasts.

What is the status of this habitat in Scotland?

Flame shell beds are vulnerable to mechanical disturbance, particularly from bottom trawls and dredges, and extensive beds are now rare. Primarily associated with areas of accelerated tidal streams the best known examples occur within a number of sea lochs on the west coast of Scotland – Lochs Fyne, Sunart, Carron, Creran, Alsh, Broom and lower Loch Linnhe.

Are we doing anything to look after flame shell beds in Scotland?

Flame shell beds are a priority UK Biodiversity Action Plans habitat now taken forward by the Scottish Government as part of the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy . This habitat is an SNH priority for marine conservation action (‘Priority Marine Features (PMFs)’ and ‘HAF’ work programmes) and will be subject to new protection efforts deriving from the Scottish Marine Bill (incl. Marine Spatial Planning and new Marine Protected Areas)

Cold-water coral reefs

Coral reefs are not just confined to the tropics – we have our own here in Scotland! Like warm-water corals, cold-water ones have a beautiful hard skeleton, and can form huge reef structures with many associated animals depending on them for shelter and food. Unlike tropical reef-building corals, cold-water corals can grow in the dark, in deep, cold water, catching their own food. Lophelia pertusa is the only reef-forming coral in British waters.

Why are they important?

Cold-water coral reefs form oases of food and shelter on the seabed, and are thought to be breeding grounds and refuges for many commercial fish. Video surveys have revealed the reefs to be home to numerous fish, including redfish, ling, tusk and pollack amongst the living coral, while ling and wolf fish?were seen in the dead coral framework. Pregnant redfish may use the reef as a refuge or nursery ground. This abundant fish life makes the reefs a target for fisheries. A wide range of invertebrate animals are also associated with the reefs.

Why do they need protection?

The reefs are slow-growing, fragile and easily damaged – thousands of years of growth can be destroyed in a few minutes by heavy fishing gear. The reefs may take centuries to recover, if at all. Recent increases in fishing for deep-sea species including redfish and grenadiers have devastated some coral reefs. In Norway, an estimated 30-50% of coral was partially or totally destroyed by bottom trawling before laws were introduced in 1999 to protect 970 square kilometres of reefs from destructive fishing activities. In the UK, trawling was banned in 2003 as an emergency measure on the Darwin Mounds, 100 square kilometres of coral reef north-east of Rockall, in response to publicity over the threat to the reefs. The ban was made permanent in 2004, but covers only a small area of reef. Other potential threats to coral reefs include oil and mineral exploitation, and the laying of cables and pipelines.

The OSPAR commission ?for the protection of the marine environment of the north-east Atlantic has recognised Lophelia pertusa reefs as a threatened habitat in need of protection. The reefs are a priority habitat for UK Biodiversity Action plans , now taken forward by the Scottish Government as part of the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy . Lophelia pertusa is listed under CITES Appendix ll.

Where are the reefs?

Lophelia pertusa has a wide geographic range from 55S to 70N, typically in water temperatures of 4-8慢, and has been found as deep as 4,000m. Off Britain, reefs form mainly on continental slopes at 200-400m deep, west of Scotland and Ireland. However Lophelia has also been found in shallower water above 150m in several places, notably near Barra and Mingulay, where a complex of reefs covers an area of approximately 100 square kilometres. These reefs are over 4,000 years old, and recently established coral colonies suggest recruitment is still occurring. To the north, reefs occur along the length of the Norwegian coast, including one 13km long and up to 30m high. The shallowest known reef is at 39m (128ft) in Trondheimsfjord.

Where can they grow?

Lophelia larvae initially need hard surfaces to settle on. This can be old reef material, so that once started, the reef is self-sustaining. The reefs can be associated with old iceberg plough-mark zones, where hard glacial deposits have been exposed. The coral grows best on sloping seabeds where there is a strong current. Small coral clumps have been found growing on the legs of oil production platforms in the North Sea, and on submerged drumlins north of Shetland

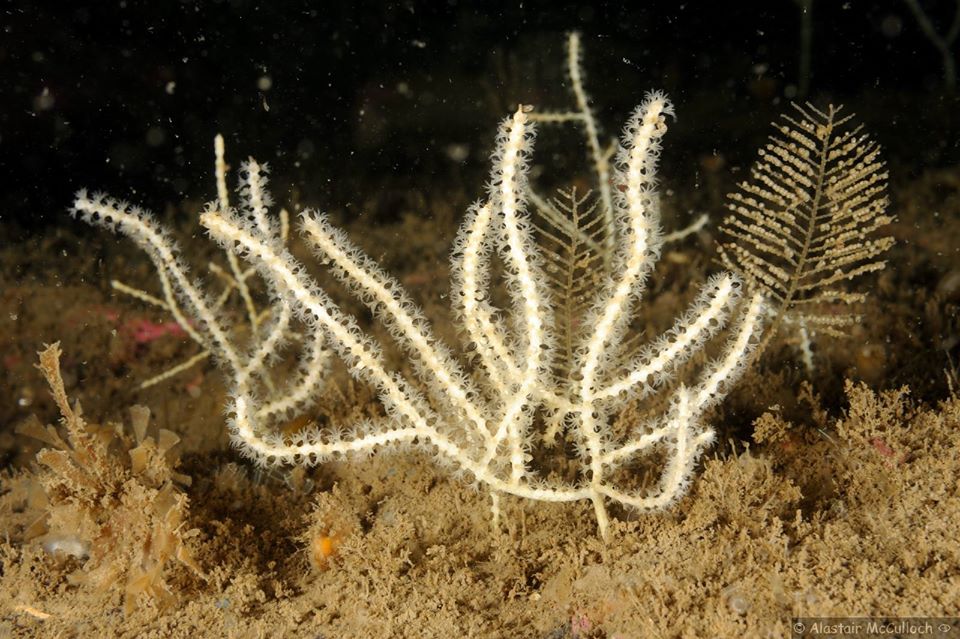

Nature of the coral

Lophelia pertusa is a beautiful coral, with a pure white, highly branched skeleton. The branches end in a cup 5-10mm across, containing a small polyp with 60 or more translucent tentacles, used to trap food. The living tissue is usually white, but can be pink or orange. The coral grows slowly, only about 6mm per year; the age of older reefs has been estimated at more than 8500 years

In British waters, the bushy colonies grow up to 5-10m across, and may be fixed to the seabed or free. After growing to a diameter of around 2 metres, the colony tends to break under its own weight, but can continue to grow, the older parts of broken pieces being colonised by sponges and other animals. Below the reef is a zone of coral gravel. The reefs have a highly diverse associated fauna, with 614 animal species recorded from Norwegian reefs, including sea fans, sponges, large bivalves, prawns, squat lobsters, basket stars and worms.

Serpulid reefs

Where are they found?

Two loughs on the west coast of Ireland contain a restricted area of small reefs, and they have been reported from a coastal lagoon in Italy. There were previously reefs in Linne Mhuirich, Loch Sween, but these died out in the 1990s for reasons that are still not understood, and now only the dead worm tubes remain. Small aggregations of organ-pipe worms were found in Loch Teacuis, Morvern in 2006, these are not yet reefs, but may grow larger and proliferate to cover a greater area of sea bed. By far the best developed and largest area of serpulid reefs in the world occur in Loch Creran, west Scotland just north of Oban

The serpulid reefs in Loch Creran grow at depths of between 6 and 10m, and up to 75cm high and 1m across. The reefs form a high-rise home for a host of other animals, especially on a muddy seabed where there are few other places to hide or attach. Bright orange sponges with long tendrils are particularly abundant on some colonies, and sea firs, sea squirts and seaweeds also attach to the tubes. Spider crabs, squat lobsters, hermit crabs, starfish, small urchins and marine snails shelter or hunt on the colony, while the bristly arms of brittlestars and long, mobile tentacles of terebellid worms reach out from deep within.

Threats

Serpulid reefs are very fragile and extremely vulnerable to mechanical disturbance, for example from mobile and static fishing gear, movement of anchors and mooring chains and even divers’ fins. They may also be sensitive to water quality and changes in water flow.

Protection

Because serpulid reefs are so rare they are protected by a UK Biodiversity Habitat Action Plan . Loch Creran is also designated as a Special Area of Conservation (SAC) for its reefs, including the worm reefs

Loch Creran is managed by the Argyll Marine SAC Management Forum. The Forum coordinated by Argyll and Bute council has produced a Management Plan for the loch. The Management Plan includes a zoning map for fishing activity, a “Moorings Pack ” to help locate mooring blocks where they will not damage the serpulid reef, and guides to anchoring and diving safely in the loch.